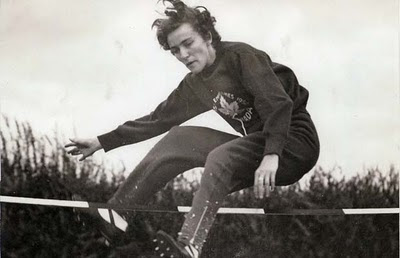

Shirley Gordon (later Olafsson) developed an unorthodox style of a scissor leg-kick to compete in the high jump. Born with a defect to her left foot, she needed to take off and land on her right. She represented Canada at the 1948 Olympics in London.

Special to The Globe and Mail

September 22, 2011

To appreciate Shirley Gordon Olafsson’s athletic career, you need to know this statistic — her right shoe is size 9½, her left 5½.

She was born with a deformed foot, enduring a series of operations and corrections through her childhood. She spent spent long, lonely weeks at the Crippled Children’s Hospital on Hudson Street in south Vancouver, which opened its doors a year after her birth in 1927.

A clunky boot with metal braces drew attention to a shy, self-conscious child.

Despite the many surgeries and treatments, the foot remained withered, the ankle locked in place, the calf muscle weak.

Though she walked with a pronounced limp, the girl determined to play sports. It looked like fun.

|

| Shirley Gordon Olaffson. (Photo by Rafal Gerszak.) |

She got selected last for pickup teams. During basketball games, she sat on the end of the bench waiting for a call that never came. A cruel field hockey coach told her she’d be more useful as a goalpost than as a player.

Mrs. Olafsson, now 84, remembers the rejection as though it happened yesterday.

“Nobody wanted me anywhere,” she said.

If teams would not find a roster spot for her, then she would find an individual sport.

Sprinting was out, as was distance running. She tried the high jump. At first, she was terrible. But she saw some potential in herself and began training on her own after school, dragging out the equipment and digging a landing pit of loose sand to ease her fall on the other side of the bar.

Later, a neighbour built a bar and pit unfortunately located on a downhill slope, making the landings somewhat perilous.

In those days, the style of jumping was known as a scissors kick, as the jumper ran to the bar before swinging one leg over to be followed by the other. Her routine was complicated by the need to take off and land on the same foot, an unorthodox style.

“I kind of hopped over the bar on one foot,” she said.

When a sprinter friend was invited to join a prestigious track club sponsored by the Hudson’s Bay Company, the youth agreed to join if she was allowed to bring along Shirley. Soon, the pair were training under experienced coaches at Brockton Oval at Stanley Park.

“I figured if I worked harder than anybody else, maybe I could do it,” she said.

She won her first ribbon in the inter-city high school championships at Hastings Park in 1943. A few years later, she finished second at the Canadian championships, earning a coveted berth on the Canadian team for the 1948 Summer Olympics to be held in London.

Headlines told the story: “Crippled girl becomes B.C. Olympic star” and “Transformation of cripple into star athlete.” Maxwell Stiles, a well-known Los Angeles newspaper columnist, described her as “a gallant girl.”

The first post-war Olympics were a Spartan affair. The Canadian team crossed the Atlantic in steerage, bringing with them their own supplies for a Games to be held in a capital still rationing food. (At the games, the high jumper discovered a cache of American bread, helping herself to a modest amount.)

The high jump was held before 60,000 spectators at Wembley Stadium. She cleared 4-foot-11 (1.5 metres), finishing tied for 11th, watching from the sidelines as Alice Coachman, of Albany, Ga., battled British housewife Dorothy (née Odam) Tyler. The American won, becoming the first black woman to claim an Olympic gold medal. Tyler is the only woman to win an Olympic medal before and after the Second World War.

Two years later, the Vancouver jumper tied for fifth at the British Empire Games in Auckland, New Zealand. On her return, she continued to play basketball and to coach her two favourite sports. She married Herbert Olafsson, a basketball star from Winnipeg who represented Canada at the world championships in Brazil in 1954 and Pan Am Games in Chicago in 1959.

Mrs. Olafsson’s feat was an early example of a British Columbian overcoming adversity to succeed in sport.

Doug Hepburn, born cross-eyed and with a club foot, took up weightlifting as a response to schoolyard taunts, in time claiming the title of World’s Strongest Man; Doug Mowat convinced his employer to sponsor the Vancouver Dueck Powerglides, the province’s first wheelchair basketball team; Rick Hansen circled the globe in his wheelchair; one-legged Terry Fox inspired a nation by trying to run across its vast expanse. Thousands took to the streets last weekend to raise money for cancer research in his name.

They all showed the same determination as Mrs. Olafsson, a widow who exercises daily and still curls once a week. She walks with a limp to this day.

Three years ago, she was one of 10 Canadians invited to run in China as part of the Paralympic torch relay. She also took part in a torch relay near her Richmond home before last year’s Winter Olympics in Vancouver.

Now, she wants to run a segment of the torch relay when the Olympics return to London next year.

She is waiting to hear from organizers. They should know that she is not one to calmly accept rejection.

Shirley Gordon Olafsson was inducted into the B.C. Sports Hall of Fame in 2004. She was also a player with the national champion Vancouver Hedlunds basketball team of 1944-45, which was inducted into the hall in 1989.

No comments:

Post a Comment