Special to The Globe and Mail

March 1, 2011

VICTORIA

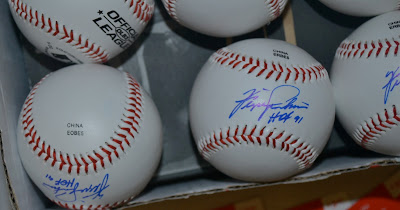

Ferguson Jenkins gripped a baseball in his left hand before signing his name in tight script. He added the notation, “HOF 91.”

Twenty seasons have passed since he was named to the Baseball Hall of Fame at Cooperstown, N.Y., the only Canadian so far to have entered the pantheon of baseball immortals.

At 68, he has known his share of honours, having won a Cy Young Award as a pitcher and an Order of Canada for his athletic prowess and community works. Now he has one more — he is depicted on a Canadian postage stamp.

Mr. Jenkins completed a month-long, cross-Canada tour on Saturday, an odyssey that was surely the longest road trip of his career. He made 41 appearances in 23 cities in nine provinces. The audiences ranged from 867 at a junior hockey game in Summerside, P.E.I., to 600 at an event in his hometown of Chatham, Ont., to the 40 who attended a brief talk and autograph session at the Gordon Head Recreational Centre in suburban Victoria.

He signed baseballs and sold paraphernalia to benefit his eponymous charitable foundation. The son of a Barbadian immigrant father and a mother whose family came to this land along the Underground Railroad as escaped slaves, Canada’s greatest ballplayer has been placed on a postage stamp to mark Black History Month.

|

| Ferguson Jenkins in Victoria. |

His reception in Victoria was considerably warmer than that afforded the pitcher early in his career as a professional.

His introduction to segregation — to Jim Crow laws — came during his first spring training in Florida in 1962.

“We didn’t eat in the restaurants, couldn’t stay in the same hotels,” he said.

At Miami Beach, black players were barred from enjoying the sands for which the town got its name. The restriction did not bother him.

“I didn’t need a tan,” he quipped, “so why go to the beach?”

He was aged 20 when assigned to the Arkansas Travelers, a minor-league team based in Little Rock. Only six years earlier, an angry mob of violent whites confronted nine black students seeking to attend Central High School.

Those same elements did not welcome black athletes. On Opening Day in 1963, white supremacists picketed the ballpark with signs reading, “Don’t Negro-ize baseball.” Other signs included foul epithets.

“At the airport,” Mr. Jenkins remembered, “there were a couple of banners that said, ‘We don’t want black players.’ ”

Only those banners did not use the word black.

“It was a shock at the beginning. But I’d read about it in the paper, so I was used to it. We knew it was going to happen. They told four of us in spring training that we were going to Little Rock and could we handle the pressure.”

He was joined in integrating Arkansas baseball by the slugging Dick Allen, of Wampum, Penn., and fellow pitchers Marcelino Lopez, a Cuban, and Richard Quiroz, a Panamanian.

“The pressure was not on the field,” he said. “It was off the field.”

The “idiots” responsible for the banners became less obvious once the team began winning. “They embraced us after awhile,” he said.

(The Travelers also included another British Columbian on the roster in Gerry Reimer, whose son, Kevin, would spend six seasons in the majors.)

Mr. Jenkins survived the test and graduated to spend 19 seasons in the major leagues, most notably with the Chicago Cubs. He won 20 games or more in seven seasons, earning a reputation for pinpoint control.

In Victoria, Mr. Jenkins was introduced by Doug Hudlin, 88, a longtime umpire who was the first non-American invited to work a Little League World Series game at Williamsport, Penn.

Mr. Hudlin, a descendent of the Alexander family, pioneer settlers on the Saanich peninsula, remembers when black residents of Victoria could not freely attend events in the city. Dance halls were barred to blacks, as were some hotels.

His father worked as a shoeshine man in the basement of the Empress Hotel. He was not permitted to pass through the lobby.

Like others, Mr. Hudlin found on the baseball diamond a place where the only colour that mattered was the one on his uniform.

“Everything was baseball,” he said, “once you were on the field.”